Introductory Philosophy

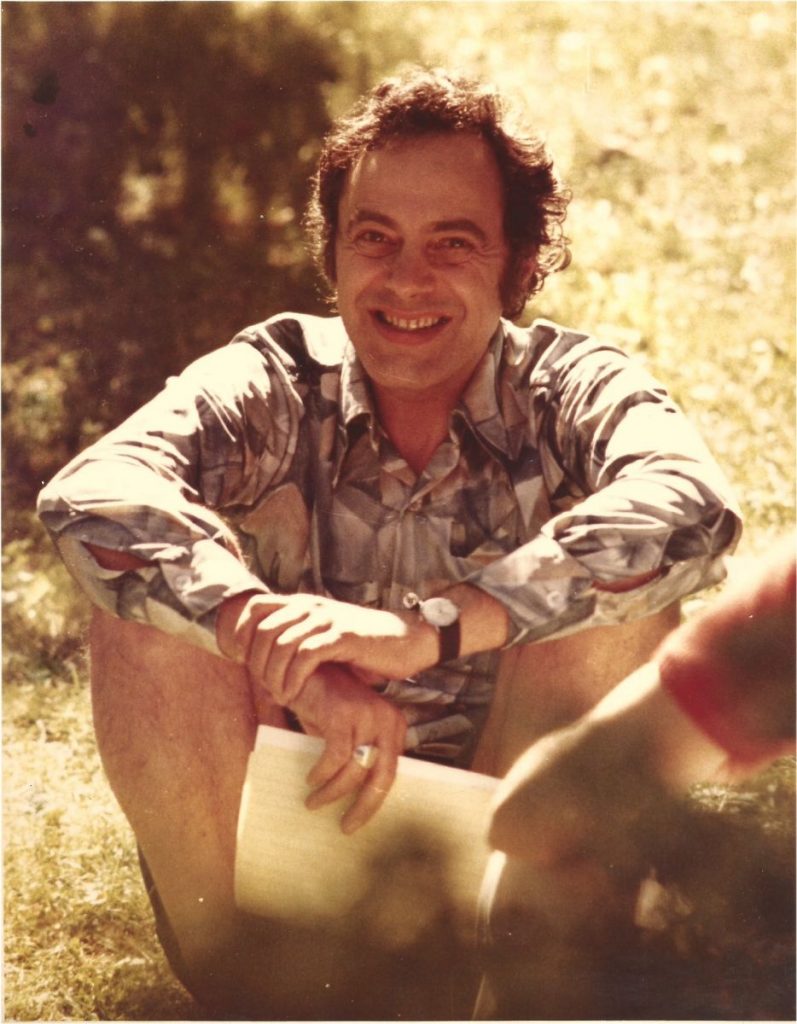

Remembering Gene Gendlin

Greg Madison

I cannot imagine coming up with an obituary or a memorial for Eugene Gendlin that he could stand to read. He would make a joke of any attempt to aggrandise his accomplishments and would often point out his own foibles and failings. He asked his son Gerry to remind people at his funeral that he was divorced and a smoker, to counter any attempts to beautify his memory.

Similarly, I know it would be impossible to offer an explanation of Gendlin’s philosophy that he could accept. He was rarely satisfied with any explication of his philosophy, including his own. I remember the strain of co-writing a chapter with ‘Gene’ for a book on Existential Therapy (Madison & Gendlin, 2011), based on an interview with him at his home in Stony Brook, New York. I wanted us both to be happy with the chapter, and engaged in endless frustrating email correspondence to no avail. In the end, I salvaged most of the dialogue and put in a disclaimer at the beginning of the chapter so Gene didn’t feel he had to stand behind what I wrote; it freed us up to not have to agree with each other.

One of Gendlin’s main concerns was that his philosophy and Focusing, the practice that derives from it, would end up described in old terms and thereby lose its fresh significance. Every word needed to be redefined in order to capture the level of ‘implicit experiencing’ that Gendlin was retrieving. He wanted each concept to be philosophically, in fact empirically, derived, not just given and believed. Every word had a fresh meaning in the ongoing dialogue, “and what do you want that word to mean?” was a constant refrain.

Gendlin lived his philosophy. Conversing with him was a profound experience. He spoke with everyone as an equal, never resorting to any kind of authority he might claim as a renowned philosopher and respected psychologist. I experienced Gene as open, generous, and deeply democratic in his approach. Philosophy and psychology and psychotherapy should be in everyday language as much as possible, accessible to everyone, not just academics or those who could afford a specialised education.

I learned Focusing in 1981 during my undergraduate psychology degree in Canada. I used Focusing in the methodology of my honours thesis research, an attempt to invite a deeper than usual ‘reflection on personal mortality’. For me Focusing was always tied to Existentialism and to attempts at an ‘everyday phenomenology’ that would add some richness to living and deeper awareness of the context of human existence.

Why did Focusing appeal to me? Focusing, and a person like Gene Gendlin, was what I had been looking for my whole life. Since childhood, and without much encouragement, I had held onto my felt sensing ability. I had this inner space where the world could not crowd in and change what I felt, but that was not the same as believing that what I felt really counted. No matter what behaviours, appearance, achievement, beliefs, the world around me insisted I adopt, there was a little space of freedom inside of my stomach and chest where I could have my own private feeling of being alive.

So what did Gendlin and Focusing add? Gendlin was the first person to describe this inner felt sensing, and how to attend to it, but most importantly, Gendlin said that this bodily sense was more valuable than just following external authorities, concepts or doctrines. Gendlin, a famous professor, gave me permission to live from this bodily feeling of rightness inside. This was radical. It undid the oppression of external authority. It allowed me to think for myself, without apology. I could just say “hmmm that doesn’t quite feel right for me somehow”, I didn’t even need to know why! Of course, I could be compelled to obey the powers that be, but I could still have a developed and sophisticated sense of why they are wrong and what would be a better direction, for me.

Focusing has an element of anarchism, as distinct from chaos. As a movement, it grew out of the turbulent 60s when American university campuses were erupting in protest and revolt. Gendlin knew that telling people what to think, or just offering new concepts, resulted in little change. People had to have the means to delve in and discover for themselves what they were, who they were, and what action they could take to improve the world. Gendlin thought he could teach people Focusing and Listening and thereby give away the essentials of therapeutic change and a method for humanising political change – those were radical agendas, which he never abandoned.

Gendlin, unlike most, had no interest in convincing others to agree with his thinking. That would have been a failure – what he wanted was that everyone could discover the bodily basis of thinking inside themselves and could then come up with their own thoughts. Hearing from others was always more exciting to him than hearing his own ideas parroted back to him. He could be scathing about academia and therapy trainings where students and trainees were taught to indoctrinate themselves with the ideas of ‘great thinkers’, and were actively discouraged from adding anything more than a meagre morsel of their own ingenuity. Gendlin would say that if those dead white men could think, so can you. We don’t need students to just rearrange what’s already in the library, we need them to think freshly for themselves.

Focusing, as described by Gendlin, is a gentle yet powerful way to pay attention to the unfolding experiential process that is felt in the body. Through this attention, it becomes clear that the human being is “unfinished living” constantly moving into new experiencing in interaction with the whole world around us. Focusing can be a meditative process for personal growth, a deep therapeutic change process, a form of embodied thinking, a bio-spiritual process, a way of accessing creativity, etc. To learn about Focusing it’s good to start with Gendlin’s original book, Focusing (1981).

Gendlin’s Philosophy of the Implicit offers a radical re-thinking of the psychological-subjective, and a re-conception of the world from the viewpoint of process (rather than set units). To get started with Gendlin’s philosophy, see either his main work, Experiencing and the Creation of Meaning or perhaps Language Beyond Postmodernism, a series of philosophical essays on Gendlin’s philosophy with Gene replying to each philosopher.

The best way to begin, of course, is with your own experience. You cannot understand Gendlin’s thinking unless you learn the process of Focusing for yourself. Focusing can be learned from various teachers and therapists around the world in workshop settings or online, most would make sure that finances do not preclude you from attending. Some resources are below.

The best tribute to the life and work of Eugene Gendlin would be if someone were to learn Focusing or something like it (he was never pushing Focusing as the only way) and from their own experiential understanding, write why Gendlin was wrong about everything. I could imagine Gene laughing and enjoying that very much.

Eugene Gendlin died May 1st 2017 in his home in Stony Brook, age 90. He was born in Vienna and fled with his family as a young boy to America ahead of the Nazi occupation. He spent most of his academic life at the University of Chicago.

References:

Gendlin, E.T. (1981). Focusing (second edition. New revised instructions). New York: Bantam Books.

Madison, G & Gendlin, ET. (2011) ‘Palpable Existentialism: An Interview with Eugene Gendlin.’ In Existential Therapy. Barnett & Madison (Eds.)

Resources:

For a more traditional account of the life and work of Eugene Gendlin, see:

https://www.eugenegendlin.com/about/

Gendlin, E.T. (1962). Experiencing and the creation of meaning. A philosophical and psychological approach to the subjective. New York: Free Press of Glencoe. Reprinted by Macmillan, 1970.

Gendlin, E.T. (1996). Focusing-oriented psychotherapy. A manual of the experiential method. New York: Guilford.

D.M. Levin (Ed.), Language beyond postmodernism: Saying and thinking in Gendlin’s philosophy. Evanston: Northwestern University Press.

Gendlin Online Library, free access to articles:

http://www.focusing.org/gendlin/

Learn Focusing: